Cloud Masking: Why a Binary Choice Breaks a Continuous Problem

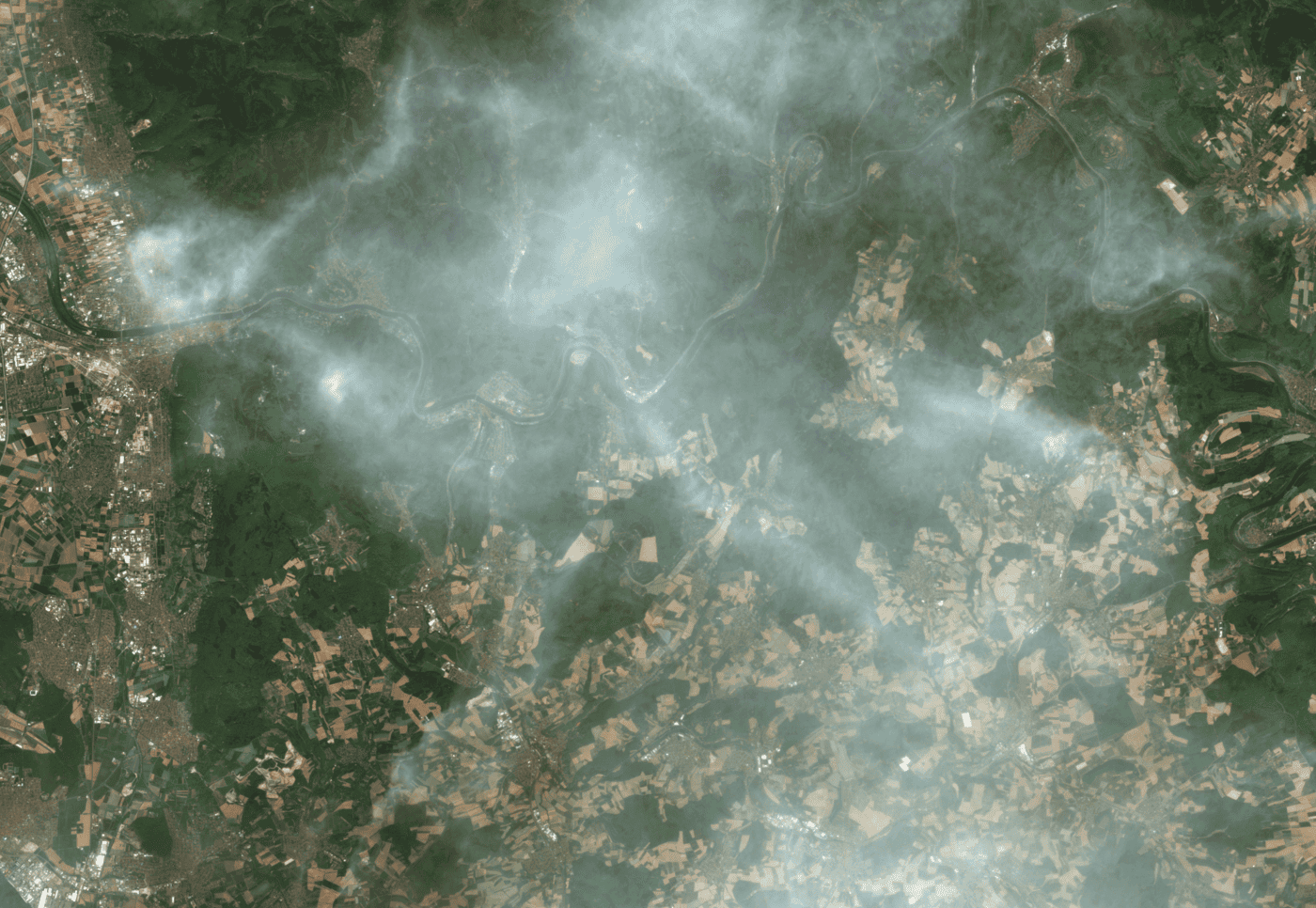

2025-08-09 · 3 min read · Cloud Masking · Haze · Sentinel-2

TL;DR: Cloud and haze exist on a spectrum, but most cloud masks make a binary decision. Set the threshold too strict and you lose signal; too loose and contamination slips in. A weighting approach avoids hard cutoffs.

The spectrum problem

Real scenes almost never split neatly into “cloud” and “no cloud.” You’ll encounter thin cirrus, veiling haze, bright soils, snow, aerosol plumes, and adjacency effects near cloud edges. Modern detectors produce a probability of cloud or shadow; it becomes a hard mask only when you pick a threshold. That conversion is where trouble starts. A high cutoff creates gaps and “Swiss-cheese” time series by discarding slightly hazy but still useful pixels. A low cutoff keeps coverage but lets thin cloud depress reflectance and indices. These trade-offs are well documented in cloud/shadow algorithms such as Fmask for Landsat and in intercomparisons of cloud masks used across sensors. USGS Landsat: Cloud Masking (Fmask/CFMask) · CEOS cloud mask intercomparison (CMIX)

Cloud shadows add another layer of ambiguity. They are low-signal, not zero, and over dark surfaces like water or forest they can be mistaken for real variability unless geometry and terrain are accounted for.

Why binary masks hurt time-series

Binary cutoffs make pixels flip in and out of a series as conditions change slightly from one date to the next. The result is temporal “flicker,” especially during cloudy seasons. Even when a pixel remains, thin haze subtly reduces contrast and pushes vegetation or water indices downward. If some dates are strictly masked and others are permissive, trend lines inherit both missing data and biased data, which is a bad combination for monitoring or compliance.

Thresholds in practice

Most pipelines land in one of three stances. A conservative threshold protects quality at the cost of coverage. A permissive threshold protects coverage but admits contamination. Scene-adaptive thresholds do better, but they still end with a binary label per pixel and can vary from scene to scene unless carefully tuned. Dilation used to remove cloud fringes also erases valid pixels near edges; it fixes halos but increases gaps.

Haze is not cloud

Light aerosol haze is often usable if you quantify its impact. Treating all haze as cloud discards signal you might want, but ignoring haze entirely biases reflectance and indices. The right question is not “mask or keep,” but “how much should this pixel count today?”

A weighting alternative

Instead of flipping pixels on or off, assign weights based on cloud/haze probability, shadow risk, view/sun geometry, and radiometric checks. Cleaner observations dominate the estimate; questionable ones contribute less or not at all. Combine this with same-day multi-sensor inputs to recover coverage without borrowing from the future, and use near-date observations only when necessary, with their dates and weights recorded so the provenance is clear. This approach reduces holes compared with strict masking and reduces contamination compared with permissive masking.

For context on atmospheric correction and why uncertainty varies by scene (e.g., snow, aerosols, low sun), see the Copernicus Sen2Cor documentation for Sentinel-2 Level-2A surface reflectance and QA layers. Copernicus Sentinel-2: Level-2A & Sen2Cor.

When a mask still helps

Binary masks still have a place: flagging thick cloud/shadow for downstream logic, satisfying regulatory workflows that expect a cloud/shadow bit, or hiding obvious clouds in visualization layers. The key is to pair any mask with the underlying probabilities and quality layers so analysts can revisit decisions when needed.

ClearSKY in practice

ClearSKY doesn’t rely on a single hard mask in production. We fuse observations using per-pixel weighting and temporal consistency, prioritizing same-day data and, when necessary, carefully incorporating past day observations with explicit provenance. The goal is stable, date-faithful time series with fewer gaps and less contamination.